The Aparados Da serra Region

Human Presence

The foothills and canyons of Aparados da Serra have long witnessed human presence, playing a significant role in the lives of the people who have inhabited and continue to inhabit the region. These landscapes have historically served as a natural connection between the plateau and the coastal plain.

Even in prehistoric times, human populations living in the area ventured into the canyons of Aparados da Serra, as evidenced by archaeological findings featuring rock engravings discovered in several locations.

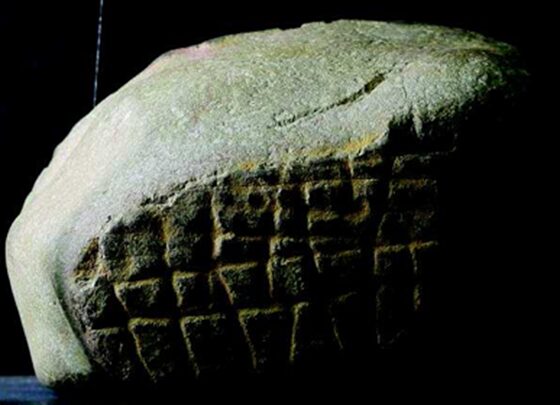

One notable example is the rock engravings found on a basalt boulder inside Malacara, which have been interpreted as signs that the area also served as a cultural expression site. These engravings, created using techniques such as pecking and polishing, consist of rectangular, triangular, and circular geometric shapes, as well as zigzagging lines.

Basalt Boulder with rock engravings recorded inside Malacara

One can also mention the archaeological artifact recorded inside Josafaz Canyon, which features rock engravings created using incision and pecking techniques. Moreover, the selected surface for the engravings underwent a polishing process, enhancing the details of the carved designs.

Archaeological artifact recorded inside Josafaz Canyon

One of the hypotheses proposed by archaeological studies suggests that the creators of these rock engravings belonged to the local populations of the Southern Jê ethnic group, represented by the Xokleng people — semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer groups who occupied the region around 6,500 years ago.

Until the colonial period, these groups continued to inhabit the canyons, slopes, and plateaus, as recorded by chroniclers and travelers. They observed that the Xokleng descended the plateau during the summer to fish and collect shellfish along the coast. However, the increasing presence of Europeans and their descendants, along with the ensuing conflicts, significantly reduced the size of these Indigenous populations, leading, in some cases, to their complete disappearance.

Another phase of human presence in Aparados da Serra was marked by Tropeirismo, an economic cycle that began in the early 18th century and lasted approximately 200 years.

To better understand Tropeirismo, it is necessary to look back on history.

In the early 17th century, the first phase of the Jesuit missions began, which included the establishment of missions by Spanish Jesuits in the region known as Tape. This area was located on the eastern bank of the Uruguay River, encompassing parts of what is now the state of Rio Grande do Sul. At the time, according to the Treaty of Tordesillas, this region was under Spanish dominion.

The Jesuit missions had cattle raising as one of their activities, with Spanish Jesuit Cristóbal de Mendoza Orellana, founder of the Mission of São Miguel Arcanjo, introducing cattle to the Tape region in 1634.

The establishment of the missions also led to the creation of a complex network of trails, which connected the missions to one another and linked them to cattle ranches, yerba mate extraction sites, and cities founded by the Spanish.

However, the Jesuit activity in the Tape region only lasted from 1626 to 1638. Expeditions led by the Bandeirantes — groups of explorers from Portuguese-controlled areas of Brazil — attacked the Jesuit missions, capturing Indigenous inhabitants. These assaults forced the Jesuits and Indigenous peoples to abandon the missions and flee across the Uruguay River.

As a result, the cattle raised in Jesuit ranches were left behind, eventually turning wild and reproducing freely, spreading throughout an area that later became known as the “Vaquería del Mar.”

Later, in the late 17th century, during the second phase of the Jesuit missions, Spanish Jesuits and Indigenous peoples returned to the territory located on the eastern bank of the Uruguay River, attempting to recover the cattle that the Spanish and Portuguese settlers now coveted.

Meanwhile, the Spanish Jesuits established the “Vaquería Nueba” or “Vaquería de los Pinares” in the Campos de Cima da Serra region, where part of the cattle from the Vaquería del Mar was relocated to.

The map below, dated 1700, shows the “Vaquería Nueba”, illustrating the paths leading from the region of the “Seven Peoples of the Missions” to Vaquería de los Pinares, in an area that is today part of the municipality of São José dos Ausentes. In the lower portion of the map, references can be seen to the “Rio que llaman Uruguay” and “Pueblo de S. Miguel,” while its upper portion depicts the outlines of Aparados da Serra, the “Laguna Grande” located in the coastal plain, and the reference to “El Mar.”

Thus, the Campos de Cima da Serra region became part of the Jesuit missions’ zone of influence, with their ranches, cattle farms, and yerba mate plantations. However, this influence was never fully consolidated, as the presence of Spanish Jesuits and the indigenous peoples associated with them was scarce in the region, and no permanent settlements were established.

At the same time, Portugal was seeking to strengthen its presence in the coastal region, which served as a link between Laguna, founded in 1676, and Colônia de Sacramento, established in 1680 on the banks of the Rio de la Plata.

This was the context in southern Brazil when, in the early 18th century, the Gold Cycle began. The intensification of mining activities in Minas Gerais created an increasing demand for cattle and mules, essential for both feeding the miners and transporting the extracted gold and other goods.

This demand led to the rise of Tropeirismo, a term referring to the movement of livestock in large herds (the “tropas”) by cattle drivers (the “tropeiros”), with cattle being transported from the fields of southern Brazil to Sorocaba, in São Paulo, and from there to Minas Gerais and other consumer centers.

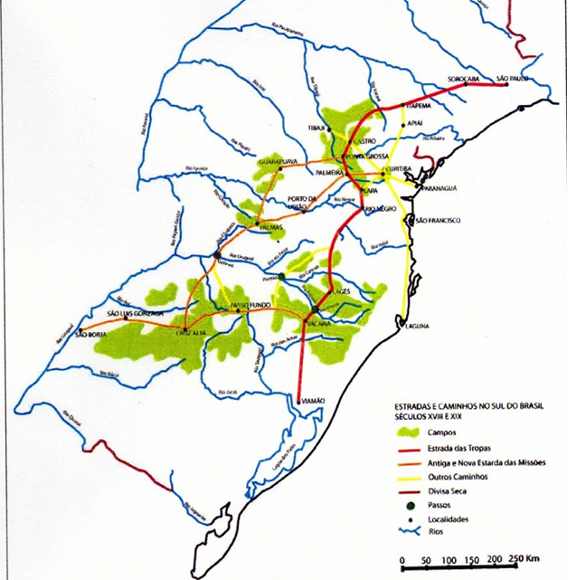

The cattle herds followed various routes, shaping the economy and cultural traditions of the region.

The oldest route, known as the “Caminho da Praia” (“Coastal Route”), was established as early as 1703, connecting Colônia de Sacramento to Laguna. This route crossed Arroio Chuí, the Rio Grande channel, and the Tramandaí, Mampituba, Araranguá, and Tubarão rivers. From Laguna, goods had to be transported by sea to São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro, which posed nearly insurmountable challenges for cattle transportation.

As a result, in 1728, another route was created: the “Caminho dos Conventos” (“Route of the Convents”). This path followed the coastline until Araranguá, then turned inland, ascending the foothills of Serra Geral via Serra da Rocinha, crossing Campos de Cima da Serra, and eventually reaching the region where Curitiba is now located.

The route that would become the most significant was established around 1731 and was named “Real Caminho de Viamão” (“Royal Viamão Route”). It originated in Viamão, passed through Santo Antônio da Patrulha, ascended the plateau via the Vale do Rio Rolante, continued through Vacaria, crossed the Pelotas River at Passo de Santa Vitória, in what is now the municipality of Bom Jesus, and then proceeded through Lajes, finally arriving in Sorocaba.

Lastly, in 1738, the “Caminho das Missões” (“Missions Route”) was established. This route originated from the fields of São Borja and passed through Santo Ângelo, Palmeira das Missões, Rodeio, Chapecó, Xanxerê, and Palmas. In Palmas, the path split into two directions, one heading toward Palmeira and Curitiba, and the other toward Guarapuava and Ponta Grossa.

Along these cattle routes, various structures were built, such as rest stops for the livestock, shelters for the tropeiros, and trading posts for exchanging goods. This contributed to the occupation and settlement of the region, which was particularly important for the interests of the Portuguese Crown. The Treaty of Madrid, signed between Portugal and Spain in 1750, enshrined the principle of uti possidetis ita possideatis, meaning that a given territory belonged to the country that effectively occupied it. The current municipalities of São Francisco de Paula, Vacaria, Bom Jesus, and Lajes, among others, trace their origins to this movement.

In the 19th century, the foothills of Aparados da Serra became a stage for events of the Farroupilha Revolution. In 1839, as they advanced towards Laguna, part of the Farrapos troops descended the plateau to the coast via the plateau slopes: Colonel Filipe de Sousa Leão descended the mountains from Vacaria, heading towards Araranguá, and Colonel Serafim Muniz de Moura descended from Lajes, traveling via the Serra do Rio do Rastro until he reached Tubarão.

Some time later, during the retreat from Laguna, General Canabarro, prevented from passing through Torres due to the presence of enemy troops, ascended the Serra do Faxinal back to the plateau.

By 1840, General Bento Gonçalves, having abandoned Viamão to avoid being surrounded by enemy forces, intended to reach the plateau to join General Canabarro, ascending Serra do Umbu in the Maquiné River valley. However, encountering enemy troops, he changed his plans, deciding instead to climb the Três Forquilhas trail. Once again blocked by enemy forces, he continued to the Mampituba River, then ascended to the plateau via the Picada do Cavalinho.

Also in the 19th century, another dynamic led to the connection between the plateau and the coast through the foothills of Aparados da Serra.

Over time, ranches were established in Campos de Cima da Serra for cattle raising, an activity carried out using enslaved labor.

During part of the year, some ranchers sent enslaved people — and occasionally some free workers who were not involved in cattle handling — to descend the mountains and cultivate agricultural products in the Mampituba River valley, in an area known as Roça da Estância (now called Mãe dos Homens). This region had fertile soil, abundant water, and a mild climate, making it ideal for farming.

Every year, a new area was selected, the native vegetation was cleared, and planting took place. After the harvest, the land was abandoned, and the process was repeated in another location the following year. The agricultural products were then transported back to the ranches by the enslaved laborers themselves, carrying the goods on their backs up the mountains, or using mules for transportation.

In this process, enslaved individuals carved out several footpaths to connect the plateau to the coast, creating routes that led from the Roça da Estância to the ranches to which they were bound.

Also in the 19th century, a settlement of runway enslaved people (a “quilombo”) was established in the region now known as Pedra Branca, the Quilombo São Roque. Initially, the quilombo was formed by enslaved individuals who had escaped from ranches in São Francisco de Paula, as well as from other areas of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina. The remote and difficult-to-access terrain provided both the isolation from authorities who might threaten their freedom, and the means for their survival, primarily through agriculture — an activity many of them were already familiar with, having worked the Roça da Estância nearby. After the abolition of slavery, former enslaved individuals who had worked on the ranches of São Francisco de Paula also settled in the quilombo, continuing their agricultural practices there.

As populations gradually settled in Campos de Cima da Serra, with the establishment of ranches and new settlements, a flow of goods began between the plateau and the coastal region. Those engaged in this trade, navigating the mountains along countless trails, were also referred to as tropeiros, as they led mule caravans. However, unlike the original Tropeirismo, in which livestock itself was the commodity, animals were no longer the traded goods but rather the means of transporting merchandise. These animals became known as “tropas arreadas” — mules trained specifically for transporting goods, in contrast to the untrained “tropas xucras” of earlier Tropeirismo.

From the plateau came charque (salted dried beef), serrano cheese, salami, wine, and pinhão (pine nuts), which were sold in the communities located at the base of the plateau. In turn, these lowland communities produced brown sugar and cachaça (a Brazilian white rum made from sugar cane), which, along with bananas, were traded with the Campos de Cima da Serra communities. These lowland settlements also served as trade hubs, where goods were exchanged and later transported to other coastal plain communities.

Agriculture and the work of the tropeiros contributed to the settlement of the lowland region. It was in this context that the municipality of Praia Grande emerged, with its territory beginning to be occupied in 1890. The area became an essential passage for tropeiros, who ascended and descended the mountains along the “Trilha dos Porcos”. Later, the market that usually took place in Timbopeba — which served as a commercial outpost connecting Campos de Cima da Serra to the southern coastal region near Araranguá, housing several dry goods and grocery stores — was relocated to Praia Grande.

In the 20th century, the timber industry flourished on the plateau, focused on native trees, particularly araucarias. Initially carried out rudimentarily in the 1930s, this activity peaked in the 1950s. The new workers employed by sawmills created a fresh consumer market for goods produced in the lowland regions, which continued to be transported to the plateau by tropeiros.

This regional tropeiro activity lasted a long time, only coming to an end with the construction of roads connecting the coast to the plateau — especially the Serra do Faxinal road (SC-290), built in the 1970s — which marked the shift from mule transportation to motor vehicles.

In the 20th century, the foothills of Serra Geral began to attract adventurers seeking exploration and challenge.

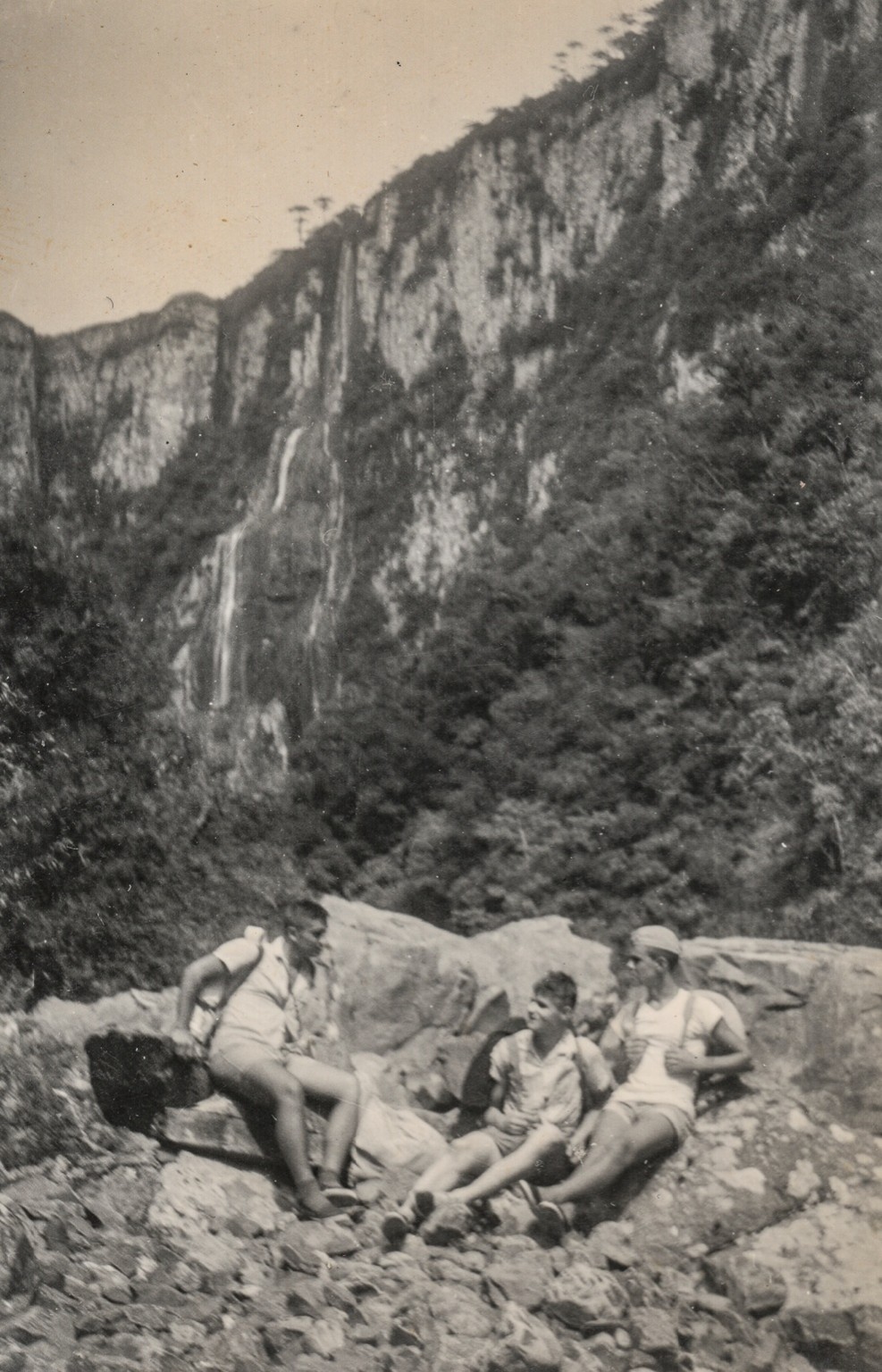

One remarkable journey was undertaken by members of the Georg Black Scout Group, who descended Serra do Faxinal as part of an epic expedition that took them from Porto Alegre — where they departed on December 27, 1914 — to Blumenau, where they arrived in early January 1915. Their route unfolded as follows. They took a train from Porto Alegre to Taquara. They continued on foot, passing through São Francisco de Paula, Tainhas, and Azulega, until they reached Itaimbezinho Canyon, where they camped to welcome the new year of 1915. They resumed their trek on foot, descending Serra do Faxinal, crossing Praia Grande, Torres, and Laguna, until they arrived in Florianópolis. From there, they boarded a steamship to Itajaí. Finally, they resumed their journey on foot, reaching Blumenau. This remarkable adventure highlights the spirit of exploration that gradually drew more people to the dramatic landscapes of Serra Geral.

Members of Georg Black Scout Group on their journey from Porto Alegre to Blumenau

A few decades later, adventurers began traversing the canyons. These traverses were made by trekking over rocks or following trails within the canyons, rather than by tracing the watercourse, as is done in canyoning. The only time they entered the water was when they had to cross the watercourse to continue along the trail on the other side. Due to the challenging terrain, these traverses usually took several days, requiring overnight stays inside the canyons.

It is known that, in the 1950s, Giuseppe Gâmbaro planned to climb the walls of Itaimbezinho. An Italian immigrant, he arrived in Brazil in the 1940s, settling in Porto Alegre, where he worked as a physical educator at SOGIPA, a local sports club. In Italy, he had been a skier and a guide for the Italian Alpine Club. He made several attempts to approach the canyon, identified an entry point, and cataloged and recorded his discoveries — but ultimately never completed the project.

The first accounts of a complete traverse of a canyon date back to 1959, when the Senior Troop of the Georg Black Scout Group from Porto Alegre traversed Itaimbezinho. Given that it is a flatter canyon, it is possible to traverse it without using vertical climbing techniques.

In the 1960s, further traverses of Itaimbezinho and Fortaleza were undertaken, mainly by members of Scout Groups from Porto Alegre, including Albert Schweitzer, Georg Black, Manoel da Nóbrega, and Tupandi.

Iberê Luiz Nodari, Geraldo Geyer, Carlos Silva and Luiz Artur Ribeiro, from

Manoel da Nóbrega Scout Group at Itaimbezinho Canyon in 1962

Throughout the 1970s, the traversing of canyons — especially Itaimbezinho Canyon — continued, and more adventurers headed that way.

By the 1980s, the traversing of canyons gained new momentum, particularly through members of the Gaúcho Mountaineering Club (CGM), with Luiz Henrique Cony playing a prominent role. They introduced climbing techniques and specialized equipment, which allowed adventurers to overcome previously insurmountable obstacles.

Later in the decade, Adventure Sport, founded by Luiz Henrique Cony and Paulo Porto, began offering basic climbing courses, which were also taken by those who were interested in traversing canyons and wanted to learn vertical climbing techniques. At that time, canyon exploration was not yet a commercial activity — it was seen as an adventure among friends, a high-difficulty trekking that sometimes required vertical climbing techniques in certain sections.

During this period, Itaimbezinho and Fortaleza continued to be traversed, and other canyons of Aparados da Serra — such as Malacara, Churriado and Faxinal — started to be explored and were traversed for the first time.

Luiz Henrique Cony in Itaimbezinho Canyon in 1980

In the 1990s, the modern concept of the traverse of canyons started taking shape. The activity evolved from being seen merely as an adventure to being recognized as a legitimate sport. Canyon traversing also became an independent discipline, incorporating specialized techniques and equipment.

Vertical techniques became more advanced, as the traverses started to involve longer rappels and more rope work. Clothing and footwear were proper for mountaineering, ensuring durability for long hikes and protection against the cold and moisture found both in the upper areas and deep within the canyons.

Mountaineering gear also became essential, including harnesses, figure-eight descenders, helmets, and equipment for rope blocking and ascents. Large-capacity backpacks were required — not just for technical gear but also for overnight provisions, as extended canyon traverses demanded camping along the route. Additionally, certain specific equipment emerged, such as jungle hammocks and special gaiters, catering to the rugged terrain and as protection against poisonous snakes.

With canyon traversing becoming more frequent, efforts were made to identify and traverse new canyons in Aparados da Serra, including Faxinalzinho, Josafaz, Pterodáctilo, Macuco, Cânion dos Índios, Cânion do Pinheirinho, Amola Faca, Rocinha, Fortuna, Serra Velha, Pé de Galinha, and Rio da Serra.

Leading this movement was a group of explorers, including Neyton Reis, Cláudia Aprato, Mauro Garcia, and Ayr Müller, all of whom helped push the boundaries of canyon traversing into a fully developed sport.

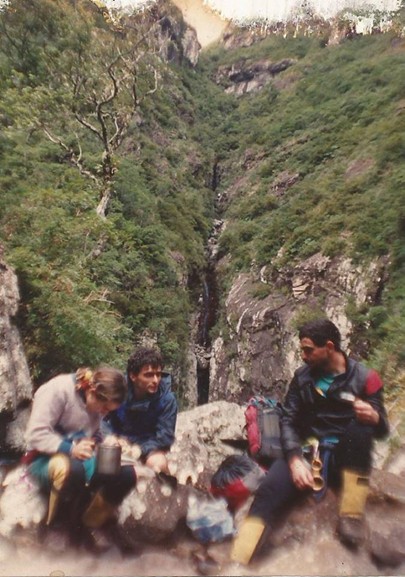

Cláudia Aprato, Ayr Müller and Neyton Reis at Cânion dos Índios in 1991

It was also in the 1990s that the commercial exploitation of canyon traversing emerged, with guides leading groups in the practice of this activity — which was presented as a strenuous trek that involved the use of vertical techniques. Organized traverses of Itaimbezinho, Malacara, Churriado and Fortaleza were set up.

Courses on canyon traversing began to be offered as well, including both theoretical and practical lessons, along with supervised traverses under the guidance of instructors. In this process, Montanha — a shop founded by Neyton Reis in 1992 — played a crucial role, becoming a center for disseminating the activity, and a place where people interested in undertaking traverses, learning the skills, or purchasing equipment would gather.

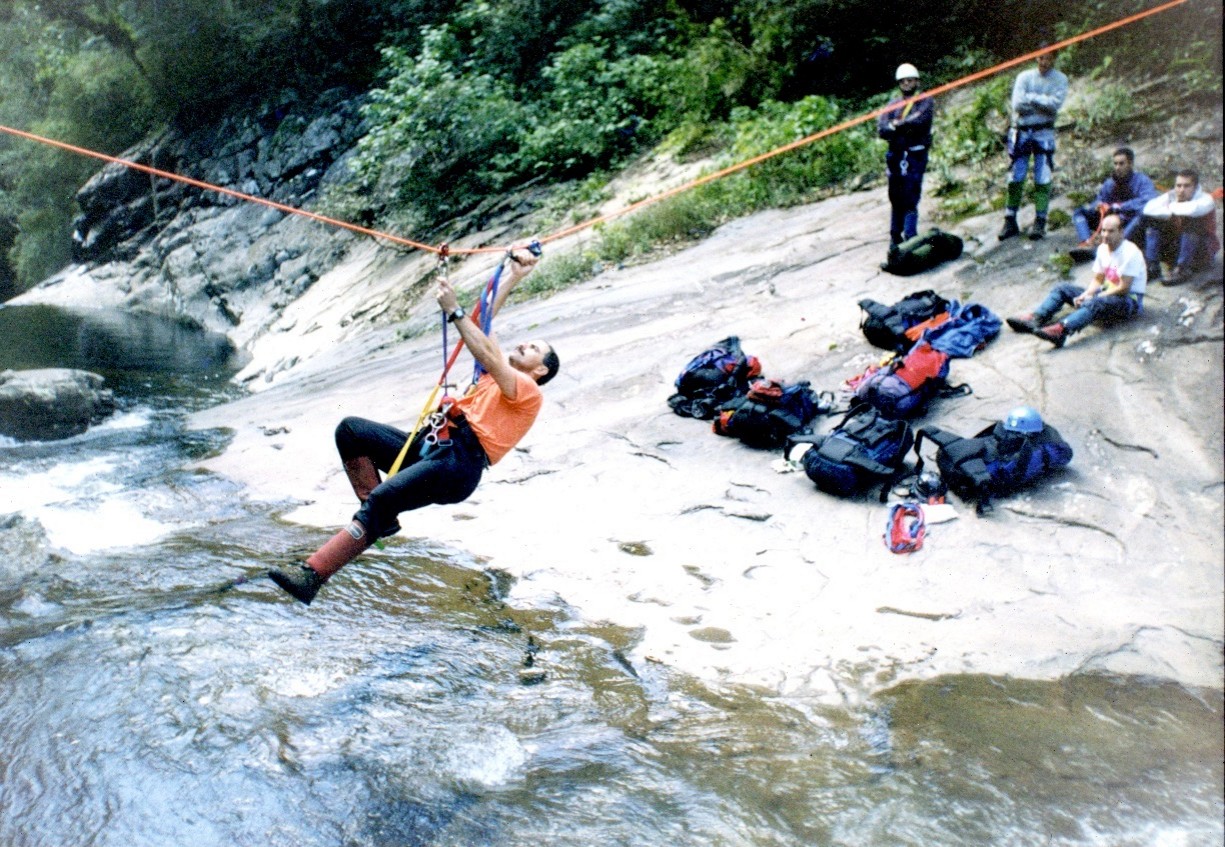

Practical lesson in a canyon traversing course at Fortaleza Canyon

Even considering the fundamental differences between the two activities, canyon traversing played an important role in the introduction of canyoning in the Aparados da Serra Geral region. It not only involved techniques that would later be used in canyoning—such as certain vertical techniques and methods for progressing through canyons—but also provided an intimate knowledge of the Aparados da Serra Geral region and the inner recesses of its canyons. It is therefore not surprising that many of those who were among the pioneers of canyoning in the region had previously practiced canyon traversing. And it should be noted that the introduction of canyoning did not mark the end of canyon traverses; they continued to take place.

Finally, also in the 20th century, the Aparados da Serra Geral region began to attract those interested in studying its unique natural characteristics, with special prominence given to Father Jesuit Balduíno Rambo.

Father Balduíno Rambo was a Jesuit priest, professor, journalist, writer, botanist, and geographer. He served as the Director of the Department of Natural History in the Culture Division of the Secretary of Education and Culture of Rio Grande do Sul, during which time he organized the Rio-grandense Museum of Natural Sciences. He was devoted to founding the Porto Alegre Botanical Garden and the Sapucaia do Sul Zoological Garden and proposed the creation of the Turvo Reserve, the first natural park in Rio Grande do Sul.

He also organized the Anchietan Institute for Research, founded in 1956, and established the magazine Iheríngia, which focused on botany and zoology. His botanical research resulted in a collection that, by 1961, comprised 65,000 samples—covering approximately 90% of the native flora of Rio Grande do Sul. In his writings, he frequently warned about the ecological issues beginning to emerge in the state, such as deforestation caused by agriculture and logging, as well as the killing of wild animals.

He authored The Physiognomy of Rio Grande do Sul, a comprehensive treatise on the state’s natural physiognomy. The work offered a detailed description of its geography along with several previously unpublished insights into its geology, flora, and fauna, and it included maps and 30 landscape illustrations derived from aerial photographs he took on flights over the entire territory of the state.

Father Balduíno Rambo on one of the aerial survey missions he carried out over the state.

In the 1940s, Father Balduíno Rambo was already venturing into the interior of Itaimbezinho Canyon, and in 1956, upon returning from a visit to American national parks at the invitation of the United States government, he stated that he was working diligently to have more National Parks created in Brazil. He remarked, “If all goes well, soon we will have a third [national park] on the eastern escarpments of Aparados da Serra, with Itaimbezinho as the initial nucleus.” His expectations were fulfilled with the creation of the Aparados da Serra National Park and the Serra Geral National Park

Geology

The region’s most prominent geological formation is the so-called Serra Geral Formation, which originated approximately 135 million years ago, in the Cretaceous period of the Mesozoic Era. According to the Theory of Continental Drift, it was in said period that South America and Africa — which back then were part of Pangea, the supercontinent that encompassed all of the continental landmasses of the Earth — began to drift apart, with the creation of the Atlantic Ocean between these two new continents. The Serra Geral Formation resulted from the superposition of successive lava flows expelled from fissure eruptions. The lava flows, when exposed to the atmosphere, cooled and solidified, turning into basaltic rocks. The flows followed one another and several layers of rock overlapped, each with an average thickness of 20 meters, reaching a total thickness that varies between 700 and 1000 meters in the Aparados da Serra region. Initially, the lava spills occurred over an immense desert. Beneath the many layers of lava, the desert sand was compacted and cemented, eventually becoming the sandstone that makes up the Botucatu Formation, which outcrops mainly at the foot of the basaltic plateau escarpment. From the plateau to the sea, there is the Coastal Plain, characterized by much more recent sedimentary deposits that started accumulating around 2.6 million years ago, in the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs of the Cenozoic Era.

The region is marked by a sharp variation in relief. The upper part of the canyons is located on the Rio Grande do Sul Plateau, in the so-called “Campos de Cima da Serra”, where the relief is gentle and undulating, with hills and shallow valleys, with altitudes ranging from 900 to 1,200 m above sea level. The lower part is located on the Coastal Plain, which has a flat relief and extends to the sea for about 40 km.

The transition between the “Campos de Cima da Serra” and the Coastal Plain is characterized by vertiginous walls, with a drop of up to 700 meters, which justify the name “Aparados da Serra” (which means something like “abruptly trimmed” plateau). The relief of this area is steep with pronounced undulations, and the altitudes range from 100 to 1000 meters.

From the edges of the plateau, when the weather is clear, it is possible to see the Atlantic Ocean and cities such as Praia Grande, in Santa Catarina, and Torres, in Rio Grande do Sul. In the middle of the Coastal Plain, it is also possible to identify several inselbergs, elevations that have resisted natural erosion processes and show that, at some point in the past, the Serra Geral escarpment was closer to the sea.

The canyons of Aparados da Serra region can be defined as river valleys with great depths, adapted to structural grooves in the area, with a cross-sectional profile demonstrating the development of deep, closed V-shaped valleys.

The development of the canyons is closely linked to the so-called faults and geological lineaments, geological structures that characterize the region’s basaltic formations. In simple terms, these structures are like large cracks that cross the various flows and layers of rock, in different directions, thus forming planes of weakness. It is along these planes that water finds a preferential path to move through and favors the processes of weathering, thus promoting its transformation into soil and facilitating the development of natural erosion processes by weakening the rock.

In addition to faults and geological lineaments, each lava flow, after solidifying into rock, formed a typical internal structure. This structure is characterized by horizontal discontinuities at the base, vertical discontinuities in the center and again horizontal discontinuities at the top. Like faults and lineaments, such discontinuities are like cracks, but are restricted to the flow itself. They also form preferential paths for water percolation, favoring weathering or differentiated alteration of the layers of the flows. Finally, also at the top, gas bubbles that were trapped during the cooling of the lava created a honeycomb structure.

Over millions of years, the weathering processes driven by rivers, the movement of groundwater through rock fractures and mass movements (landslides, falling blocks, etc.) ended up forming the canyons as they are known today.

The region is home to canyons such as Josafaz Canyon, Itaimbezinho Canyon, Faxinal Canyon, Malacara Canyon, Fortaleza Canyon, Canyon of Indios, Canyon of Molha-Côco, Churriado Canyon, Corujão Canyon, Canyon of Pedras, among others.

The canyons vary greatly in terms of length, width and depth. Itaimbezinho, for example, is 5.8 km long, up to 2,000 m wide and has an average depth of 600 m, reaching 750 m at its maximum point. Fortaleza, in turn, is approximately 7 km long, up to 2,300 m wide and has a depth that varies between 200 and 1,000 m. Malacara is approximately 6 km long, up to 2,000 m wide and has a depth that varies between 100 and 1,000 m. Finally, the Cânion dos Índios is approximately 4 km long, up to 500 m wide and varies between 100 and 1,000 m in depth.

Climate

The significant altitude difference between the coastal plain and the plateau imposes notable climatic variations in the Aparados da Serra Geral region, particularly in terms of rainfall levels and average annual temperatures. In Campos de Cima da Serra, rainfall levels range between 1,700 and 2,000 mm, and the average annual temperature is around 15°C, with a climate that can be classified as temperate. Meanwhile, in the coastal plain, rainfall levels vary between 1,300 and 1,500 mm, and the average annual temperatures range between 18°C and 20°C.

In Campos de Cima da Serra, when a strong polar air mass dominates, episodes of intense cold may occur, leading to the formation of frost and, in higher-altitude areas, even snowfall.

Another characteristic phenomenon of the region is the fog that forms along the slopes of the mountains due to the rising of warm, humid air masses from the sea. This rapid ascent causes a sudden drop in temperature, leading to condensation of water vapor and the formation of fog.

When this fog develops within the canyons, it is called “viração”, or “nada” (nothing) — as it significantly reduces visibility. Under these conditions, the combination of falling temperatures, high humidity, and wind can lead to a considerable decrease in perceived temperature, making the environment feel much colder.

The upper region of the canyons is home to numerous springs, streams, and creeks, which give rise to countless waterfalls. Additionally, depending on the amount of rainfall, temporary waterfalls may emerge, adding to the dynamic beauty of the landscape.

FLORA AND FAUNA

Given the unique physical and environmental characteristics of Aparados da Serra, the region boasts a diverse vegetation, forming a highly complex and heterogeneous mosaic that includes both forest formations and open landscapes, varying according to their specific location.

In Campos de Cima da Serra, the dominant forest formation is the Mixed Ombrophilous Forest, also known as the Araucaria Forest, characterized by the presence of the Araucaria (Araucaria angustifolia), commonly referred to as the Brazilian pine or Paraná pine. This forest is also composed of other typical species, such as the xaxim or samambaiaçu (Dicksonia sellowiana), the pinheiro-bravo (Podocarpus lambertii) and the canela-lageana (Ocotea pulchella).

In addition to these forests, the region also features grassland formations, such as Savanas Gramíneo-lenhosas (Savanna Grassland-Woodlands), where the capim-caninha (Andropogon lateralis) is predominant. Additionally, Campos de Cima da Serra is home to Turfeiras, composed of dense beds of moss (Sphagnum spp). These marshes, typically found in the moist lowlands of the plateau, play a crucial hydrological and hydrogeological role as they act as water reservoirs and regulate stream flow, contributing to the recharge of underground aquifers.

Araucaria Forest

Cloud Forest

At the edges of the plateau and along its slopes, there is a unique vegetation formation known as the “Cloud Forest of Aparados da Serra.” This ecosystem is named after the frequent presence of fog in these areas and is characterized by twisted trees, such as cambuim (Siphoneugenia reitzii), gramimunha (Weinmannia humilis), and casca-d’anta (Drimys angustifolia). These trees are typically covered in moss and epiphytes, including various species of bromeliads. On the steep cliffs, lichens also thrive, giving the rock walls their distinctive hues, ranging from white and gray to yellowish tones.

In the transition zone between the cloud forest and other ecosystems, there is rupicolous vegetation, consisting of plants such as urtigão (Gunnera manicata), cará-mimoso (Chusquea mimosa), and bracatinga (Mimosa scabrella).

In areas of the plateau slopes where the inclination is less steep, we find the Dense Ombrophilous Forest, also known as the Atlantic Rainforest, which includes tree species such as canela-branca (Nectandra leucothyrsus) and palmito-jussara (Euterpe edulis).

On the Coastal Plain, the predominant forest formation is the Lowland Dense Ombrophilous Forest, also referred to as the Tropical Forest of the Quaternary Southern Plains. Typical species in this region include jerivá (Syagrus romanzoffiana), figueira-da-folha-miúda (Ficus organensis), and ipê-amarelo (Tabebuia umbellata).

This remarkable diversity of vegetation types supports an equally rich array of wildlife. The Aparados da Serra region is home to approximately 628 cataloged species, representing a significant proportion of the total fauna in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. Additionally, many of these species are endemic to the area.

On the upper parts of the canyons, various mammals of different sizes can be found, including: pumas (Puma concolor); jaguatiricas (Leopardus pardalis); different species of deer, such as veado campeiro (Ozotocerus bezoarticus), veado bororó (Mazama nana) and veado pardo (Mazama americana); lobos-guará (Chrysocyon brachyurus), graxains-do-mato (Cerdocyon thous) and graxains-do-campo (Pseudolapex gymnocercus), bugios (Alouatta guariba) and zorrilhos (Conepatus chinga).

The diversity and magnificence of the ecosystem highlights the ecological richness of Aparados da Serra.

“graxaim-do-campo” (Pseudolapex Gymnocercus)

The avifauna of the region is also exceptionally rich and diverse, with more than 150 recorded species. In the Mixed Ombrophilous Forest of the plateau, one can find species such as the papagaio-charão (Amazona pretrei), an endemic bird of Serra Geral, the papagaio-de-peito-roxo (Amazona vinacea), the corujinha-do-sul (Otus sanctaecatarinae), and the grimpeiro (Leptasthenura). Meanwhile, in the grassland areas, species such as the pássaro-preto-de-veste-amarela (Xanthopsar flavus), the junqueiro-de-bico-reto (Limnornis rectirostris), the noivinha-de-rabo-preto (Heteroxolmis dominicana), the pedreiro (Cinclodes pabsti), the macuquinho-da-várzea (Scytalopus iraiensis), and the caboclinho-de-barriga-preta (Sporophila melanogaster) thrive, alongside Andean-Patagonian birds, some of which are endemic to Serra Geral. At lower and mid-altitude regions, typical species of the Dense Ombrophilous Forest are present, including the macuco (Tinamus solitarius), the jacutinga (Pipile jacutinga), and the sabiá-cica (Triclaria malachitacea). Finally, birds of prey are also found in the region, such as the gavião-pega-macaco (Spizaetus tirannus), the águia-cinzenta (Harpyhaliaetus coronatus), the gavião-pato (Spizaetus melanoleucus), and the urubu-rei (Sarcoramphus papa), among others.

Carcará (Caracara plancus)

The amphibian fauna of the region is generally characterized by species typical of the Dense Ombrophilous Forest and the Mixed Ombrophilous Forest, as well as species that can be found in both forest formations, including several endemic species of Rio Grande do Sul. Examples of anurofauna include the rã-das-pedras (Cycloramphus valae), the sapo-guarda (Elachistocleis erythrogaster), the sapinho-de-barriga vermelha (Melanophryniscus cambaraensis), and the rã-dos-lajeados (Thoropa saxatilis). Regarding ophidians, the most abundant ones belong to the Colubridea family, including species such as the cobra-cipó (Phylodrias patagonensis) and the cobra-d´água (Liophis sp). Less common species include the cascavel (Crotalus durissus), the urutu (Bothrops alternatus), and the cotiara (Bothrops cotiara). Finally, there is not a great diversity of lizards, with the teiú (Tupinambis sp.) being the most representative species.

Sapinho de barriga vermelha (Melanophryniscus cambaraensis)